By Dr. Michael Murray, N.D.

Astaxanthin is a vibrantly deep red carotenoid pigment found predominantly in marine life. There are over 400 different members of the carotenoid family of pigments in nature. Historically, the potency of a carotenoid in improving human health was based on its ability to be converted to vitamin A. For example, the pigment that makes carrots orange, beta-carotene, has the highest vitamin A value and was long thought of as the most important carotenoid. However, it is now known that some of the most important carotenoids to human health are not converted to vitamin A at all.

Of all the non-vitamin A carotenoids, astaxanthin is regarded as the “crowned king.” It is given this title because of its unique benefits and actions in promoting health and protecting against cellular damage, especially in the brain and vascular system.

The richest concentration of astaxanthin is found in a microalgae known as Haematococcus pluvialis. When the algae is consumed by salmon, lobster, shrimp, krill, and other sea life, the intense red pigmentation results in these animals having red or pink flesh or outer shells.

Astaxanthin is essential to the survival of these organisms. For example, astaxanthin is required by the microalgae itself to protect against the damage produced during photosynthesis – the conversion of sunlight into chemical energy. It is also known that young salmon die or do not develop properly without sufficient intake of astaxanthin in their diet. The astaxanthin also provides some protection for some animals by making them less visible in deep water, where the red segment of the wavelength spectrum of visible light does not penetrate. The red pigment also plays a role in mating and spawning behavior.

Although astaxanthin is found in salmon, herring roe, or krill oil supplements, the amounts in these sources are much lower than those provided from extracts of H. pluvialis. For example, the level of astaxanthin naturally occurring in a capsule of fish or krill oil is in the range of 100 mcg (0.1 mg). That amount is not much compared to the 4 to 12 mg per capsule found in most astaxanthin supplements derived from H. pluvialis.

To produce natural astaxanthin, large indoor tanks or outdoor glass-tube plantations are to grow H. pluvialis under ideal conditions that enhance astaxanthin production. These measures also prevent environmental contamination. After the H. pluvialis has produced astaxanthin, extraction methods are used to release the astaxanthin from the thick cell wall of the algae and concentrated.

There are other sources of astaxanthin on the market, but these forms are produced from either chemical synthesis or produced from genetically modified yeast (Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous, formerly Phaffia rhodozyma). These synthetic forms are approved as feed additives and are often fed to salmon in fish farms to give them red flesh, but the synthetic forms differ in structure from natural astaxanthin. The synthetic form is 20 times less effective as an antioxidant, so it is unlikely it has the same benefits as natural astaxanthin.1

It is a bit cliché to refer to various natural compounds as antioxidants. Yes, astaxanthin has antioxidant activity, and it helps to prevent the oxidative damage that contributes to conditions such as aging, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. And yes, so do many other natural antioxidants. But astaxanthin is a bit different from an antioxidant and exerts additional benefits to protect cells.2

First, regarding general antioxidant actions in protecting cell membranes, astaxanthin exerts significantly stronger effects than many popular antioxidants.

As a protector against oxidative damage, astaxanthin is:

In free radical elimination, astaxanthin is:

In addition to this superior antioxidant activity, astaxanthin has some special properties that make it much more functional as an antioxidant. First to mention in this regard is that one of the unique aspects of astaxanthin relates to its size and how it fits into cell membranes. It is considerably larger/longer than other popular carotenoids. Its size and physical form allows it to be incorporated into cell membranes where it is able to span the entire thickness of the cell membrane. This allows astaxanthin to not only protect the inner and outer cell membrane from oxidative damage, but also to stabilize the cell membranes.2,3

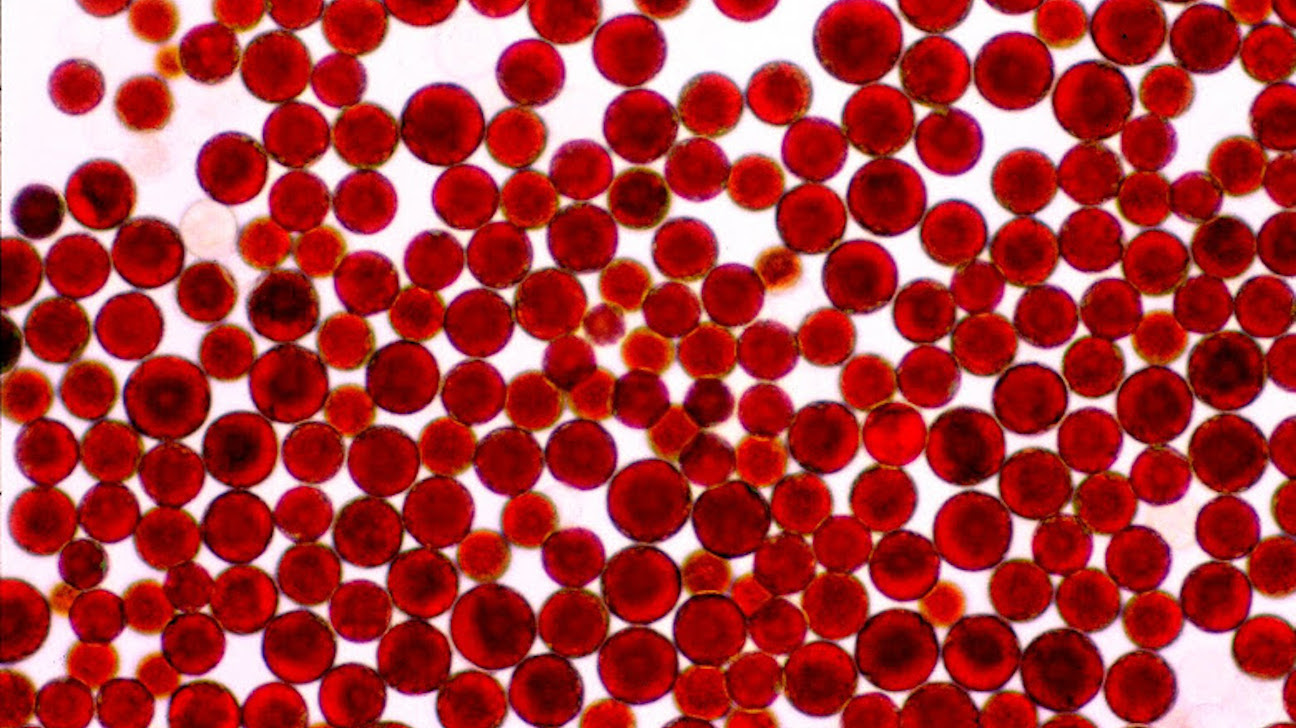

This membrane stabilizing effect is very important in red blood cells (RBCs). Because RBCs are more susceptible to being damaged by oxidative attack as we age, this can lead to impaired delivery of oxygen to body tissues. An added benefit is that astaxanthin also significantly improves blood flow. Generally, the better the oxygenation of tissue, the better the function of the individual cells and tissue as a whole.

All of these effects were shown in a double-blind study of 40 male soccer players randomly assigned to take either astaxanthin (4 mg) or a placebo daily. After 90 days, results showed a number of benefits with astaxanthin, including a rise of salivary secretory IgA levels indicating improved immune function, a decrease in prooxidant-antioxidant balance showing significant functional antioxidant activity, a decrease in muscle enzymes levels showing protection against exercise-induced muscle damage, and a significant blunting of the systemic inflammatory response as noted by a reduction in the level of C-reactive protein, which is a well-accepted blood marker for inflammation.4

The scientific research on astaxanthin includes over 50 clinical and experimental studies. The results from this research have shown astaxanthin to be helpful in:

One of the special attributes of astaxanthin is its ability to cross the blood-brain and blood-retinal barrier to protect both the brain and eyes. This effect is quite unusual for carotenes. For example, popular carotenes like beta-carotene and lycopene do not cross either barrier. This effect of astaxanthin, as well as some actions in protecting brain cells from inflammation, indicates that it may be particularly helpful in improving brain and eye health and protecting the brain against Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, and other degenerative brain and eye disorders.14

Astaxanthin also promotes the growth of new brain cells and overall brain “plasticity,” the ability of the brain to respond to different stimuli. These effects of astaxanthin explain why it not only preserves brain function during the aging process but also improves brain function as well. For example, in one double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 96 healthy middle-aged or elderly subjects were randomly selected to take either placebo, 6mg of astaxanthin per day, or 12 mg of astaxanthin per day for twelve weeks. Improvements in the score in the battery of mental tests known as CogHealth were found in the 12 mg group after 12 weeks. Improvements were noted earlier in a learning test in both the 6mg and 12mg astaxanthin groups.15

Numerous clinical studies have shown astaxanthin to protect the skin from sun damage and enhance the barrier function of skin.16

Lastly, astaxanthin also demonstrates significant immune-enhancing effects. In one double-blind clinical trial in healthy, young women averaging just over 20 years old, the women were separated into three different groups: the control group took a placebo, while the two treatment groups took either 2 mg of astaxanthin per day or 8mg per day over eight weeks. Results showed that at either dosage, astaxanthin:13

The dosage range for astaxanthin is 4 to 12 mg daily.

There are no known side effects or drug interactions at recommended dosage levels.

References